In today’s article, I give shorter answers to several reader questions. (Previous installment here.)

If my printer could literally print out money, would it have that big an effect on the world?

—Derek O'Brien

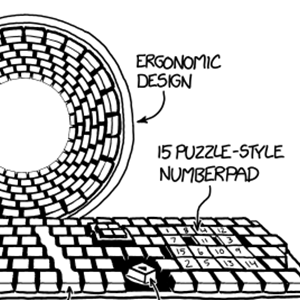

You can fit four bills on an 8.5”x11” sheet of paper:

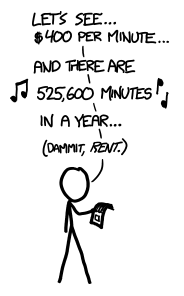

If your printer can manage one page (front and back) of full-color high-quality printing per minute, that’s $200 million dollars a year.

This is enough to make you very rich, but not enough to put any kind of dent in the world economy. Since there are 7.8 billion \$100 bills in circulation, and the lifetime of a \$100 bill is about 90 months, that means there are about a billion produced each year. Your extra two million bills a year would barely be enough to notice.

What would happen if you exploded a nuclear bomb in the eye of a hurricane? Would the storm cell be immediately vaporized?

—Rupert Bainbridge (and hundreds of others)

This question gets submitted a lot.

It turns out the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration—the agency which runs the National Hurricane Center—gets it a lot, too. In fact, they’re asked about it so often that they’ve published a response.

I recommend you read the whole thing, but I think the last sentence of the first paragraph says it all:

“Needless to say, this is not a good idea.”

It makes me happy that an arm of the US government has, in some official capacity, issued an opinion on the subject of firing nuclear missiles into hurricanes.

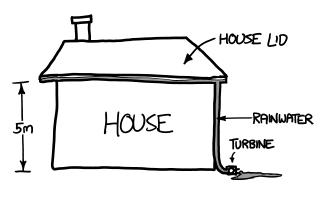

If everyone put little turbine generators on the downspouts of their houses and businesses, how much power would we generate? Would we ever generate enough power to offset the cost of the generators?

—Damien

A house in a very rainy place, like the Alaska panhandle, might receive close to four meters of rain per year. Water turbines can be pretty efficient. If the house has a footprint of 1,500 square feet and gutters five meters off the ground, it would generate an average of less than a watt of power from rainfall, and the maximum electricity savings would be:

\[1500\text{ft}^2 \times 4\tfrac{\text{ meters}}{\text{year}}\times1\tfrac{\text{kg}}{\text{liter}} \times9.81\tfrac{\text{m}}{\text{s}^2}\times5\text{ meters}\times15\tfrac{\text{cents}}{\text{kWh}}=\frac{$1.14}{\text{year}}\]

The rainiest hour on record occurred in 1947 in Holt, Missouri, where about 30 centimeters of rain fell in 42 minutes. For those 42 minutes, our hypothetical house could generate up to 800 watts of electricity, which might be enough to power everything inside it. For the rest of the year, it wouldn’t come close.

If the generator rig cost $100, residents of the rainiest place in the US—Ketchikan, Alaska—could potentially offset the cost in under a century.

Using only pronounceable letter combinations, how long would names have to be to give each star in the universe a unique one word name?

—Seamus Johnson

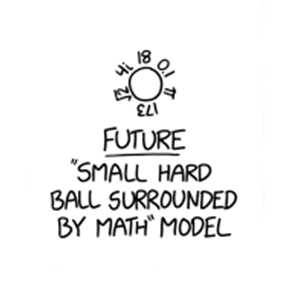

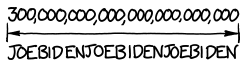

There are about 300,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 stars in the universe. If you make a word pronounceable by alternating vowels and consonants (there are better ways to make pronounceable words, but this will do for an approximation), then every pair of letters you add lets you name 105 times as many stars (21 consonants times 5 vowels). 105 possibilities per two characters is about the same information density that numbers have, which suggests the name will end up being about as long as the total number of stars written out:

I like doing math that involves measuring the lengths of numbers written out on the page—which is really just a way of loosely estimating log~10~x. It works, but it feels so wrong.

I bike to class sometimes. It's annoying biking in the wintertime, because it's so cold. How fast would I have to bike for my skin to warm up the way a spacecraft heats up during reentry?

—David Nai

Reentering spacecraft heat up because they’re compressing the air in front of them (not, as is commonly believed, because of air friction).

According to this calculator, to increase the temperature of the air layer in front of your body by twenty degrees Celsius (enough to go from freezing to room temperature), you would need to be biking at 200 m/s.

The fastest human-powered vehicles at sea levels are recumbent bicycles enclosed in streamlined aerodynamic shells. These vehicles have an upper speed limit near 40 m/s. This is the speed at which the human can just barely produce enough thrust to balance the drag force from the air.

Since drag increases with the square of the speed, this limit would be pretty hard to push any further. Biking at 200 m/s would require at least 25 times the power output needed to go 40 m/s.

At those speeds, you don’t really have to worry about the heating from the air—a quick back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that if your body were doing that much work, your core temperature would reach fatal levels in a matter of seconds.

How much physical space does the internet take up?

—Max L

There are a lot of ways to estimate the amount of information stored on the internet, but we can put an interesting upper bound on the number just by looking at how much storage space we (as a species) have purchased.

The storage industry produces in the neighborhood of 650 million hard drives per year. If most of them are 3.5” drives, then that’s eight liters (two gallons) of hard drive per second.

This means the last few years of hard drive production—which, thanks to increasing size, represent a large chunk of global storage capacity—would just about fill an oil tanker. So, by that measure, the internet is smaller than an oil tanker.

What if you strapped C4 to a boomerang? Could this be an effective weapon, or would it be as stupid as it sounds?

—Chad Macziewski

Aerodynamics aside, I’m curious what tactical advantage you’re expecting to gain by having the high explosive fly back at you if it misses the target.